By Kim Nilsen

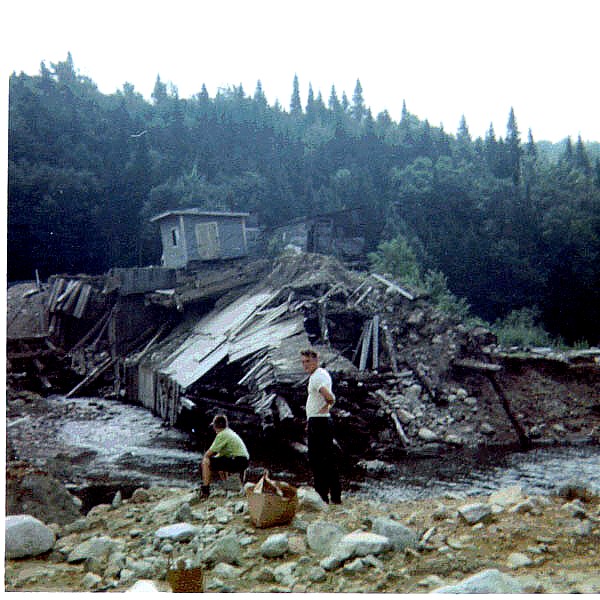

The Cohos Trail had its origins in a disaster. In 1969, the great earthen and timber crib dam that held back beautiful 223-acre Nash Bog failed utterly high in what is now the Nash Stream Forest. Several years later, the late Arthur Muise, a much revered NH Fish and Game officer and the man for whom Mt. Muise is named, spun a yarn to me about the dam breach and the great flood that destroyed the Nash Stream valley and swamped the streets and the paper mill in Groveton village. His tale was so compelling, I jumped in my tin-can Datsun as soon as I could and drove up to the old dam site.

It was my first foray into the marvelous backcountry that is the Nash Stream Forest. I began exploring that country and the lands to the north all the way to Canada after that, and by 1978 I somehow conjured up the foolish notion that perhaps there ought to be a long distance trail in that wonderful realm. Humans ought to experience that moose haunt along the central spine of Coos County, NH. Yes, they should.

So – back in 1969, after two days of downpour, Groveton Papers Company employee Ralph Rowden, who doubled as the Northumberland Township (Groveton) municipal court judge, drove nearly 10 miles up the Nash Stream Road to get to the big earthen and log-crib dam that held back the 223-acre Nash Bog Pond, a body of water created to assist the logging industry and provide a reservoir reserve for the water-thirsty mill.

In driving rain, Ralph made it to the dam and adjusted the sluice gates in the dam to ensure they were opened fully to allow the maximum downstream flow so that the water release might take pressure off the old dam. His job complete, and in a torrent of noise from the outflow through the sluice gates, he retreated to his vehicle and motored away and downhill back toward Groveton. He would not reach town that afternoon.

Less than half a mile from the dam site, the big man behind the wheel heard a sudden and loud roaring sound. He stopped his truck, opened the door, and looked upstream. Before he could see what was making the awful racket, he could barely make out treetops disappearing suddenly from view to the north. A moment later, in the vicinity of the big steel stringer bridge over Nash Stream, a tall wall of flood water burst from the sodden landscape. Instinctively, and with no time to hesitate, Ralph ran into the woods to try and find a tree to climb, in the hopes he could ascend above the torrent of water that was crashing south through the valley.

Thirty feet from the road, Ralph found his tree and with the spirit of a younger man, shinnied up the trunk and into the branches, grabbed on tight, and prayed for salvation.

Just north of him, the deluge of flood water struck, pushing hundreds of uprooted trees at the front of the current. The downed trees began to pile up and up at the head of the patch of forest where Ralph was perched. Drenched in rainwater and noise, the man could not know that the debris north of him was creating a dam of its own and diverting the flood to both sides of where he clung to the branches of the tree.

Now the fury of the flood was on all sides, tens of thousands of gallons per second slamming by and in so doing ripping the Nash Stream valley to sheds. The power of the moving water stripped very ounce of vegetation and soil from the valley floor, Hillsides undermined by the torrent caved away in landslides that are still visible in places to this day. All the great trout fishing habitat in the great stream vanished.

As evening came on, Groveton Paper Mill employees suddenly found their mill floors awash in several feet of water. Slicks of muddy and debris laced water ran through the streets of town. It was Groveton’s luck that just upstream on the Upper Ammonoosuc River, a broad floodplain opens out, and when the Nash Stream flood made it to the river, its power was dampened in the broad expanse of the floodplain floor.

Up in his tree, it began to dawn on Ralph that his choice of refuge had saved his life. As the flood began to abate, he realized that his perch would hold and he’d live through this nightmare. But now the light was disappearing, the rain was still falling. He had no flashlight to help guide him, no food, no protection overnight. So there would be no leaving his location until dawn broke.

But there was light. Blue light. It began to dance all over the ruined forest. That blue glow was indelibly etched into Ralph’s memory. He stood in awe of it. The roots of the uprooted trees began to slimmer in places with blue foxfire. Luminescent microbes filled the woods with silent blue sparks and speckles. The big man was grateful for the hour or two of the lively blue dance of light.

As soon as dawn played out enough light for Ralph to see, he set off downstream, picking his way through a moonscape of forest ruin. In most all but the highest places the road was completely destroyed and the land below its surface utterly washed away. He estimated he may have walked half the distance to the junction with the Emerson Road far down the valley when he was met by townspeople moving north to try to find him.

In his municipal courtroom in the basement of the library in the later years of the ‘70s, Ralph relayed his story to me. I was spellbound by his words. Five years earlier I had motored up the rebuilt Nash Stream Road, spurred on by a tale from NH Fish and Game officer Arthur Muise, to see for myself the savaged valley, the crippled dam site, and the vast mud plain that was the lake floor of Nash Bog. Now I had a first-hand account of the disaster to match what I had witnessed in the valley.

Ralph is gone now. So is Arthur Muise. But I am grateful to them for their stories, their warm personas, and their influence on me and the Cohos Trail. I make a pilgrimage into the upper Nash Stream valley several times a year, and hope to until I wash away for good. Love that wild place with every fiber of my being.